The Immortal Storm

A History of Science Fiction Fandom

by Sam Moskowitz

Fantasy Commentator, 1945-1952

Atlanta Science Fiction Organization Press: 1954

269 pages

Hyperion: Westport, Connecticut

1974 & 1988

Science fiction's self-organized fandom

No other field or genre of literature has anything quite like science fiction fandom attached to it. When Hugo Gernsback started the first all-science-fiction magazine, Amazing Stories in 1926, he included reader features and a letter-column with full addresses. Readers were encouraged to participate, get in touch with each other, learn more about science, and start correspondence clubs and local branches.

No other field or genre of literature has anything quite like science fiction fandom attached to it. When Hugo Gernsback started the first all-science-fiction magazine, Amazing Stories in 1926, he included reader features and a letter-column with full addresses. Readers were encouraged to participate, get in touch with each other, learn more about science, and start correspondence clubs and local branches.

The history of organized fandom from 1926 through 1939 is told in a unique book, The Immortal Storm: A History of Science Fiction Fandom, by Sam Moskowitz. Many writers and artists, editors and publishers, have devoted much time and care to science fiction since the 1920s.

Sam Moskowitz I'd call a tireless promoter of the field more than any one of those more specific functions. Moskowitz's latter teenage years coincide with the latter 1930s; he's a major participant in a lot of the fan history here, particularly the last several years when the first tiny science fiction conventions were held. (Forrest J. Ackerman, also in these pages, is another pioneering, lifelong, and tireless promoter.)

Then as now, the great majority of readers of the professional science fiction magazines never become involved in fannish activities: writing to other fans, publishing fanzines, joining a club. These fifty or a hundred active fans are very young, many in their late teens. I suppose that by the first World Science Fiction Convention in 1939, they average around twenty years old. Since the 1930s are Depression years with minimal spending money, almost all fans' national contacts were via correspondence and fanzines.

The main physical concentration was in the New York City - Philadelphia - Newark area. Clubs were begun, factionalized, taken over, split, merged, and collapsed. Fanzines appeared and died with bewildering rapidity.

The critical early cultural split among SF club-goers was whether any given organization was to be devoted to science education and science hobbies, or to discussion of science fiction itself. Or some mixture. A later source of major acrimony was whether the fans should embrace Communism, promote Communist causes and so on. Technocracy and Esperanto were other issues as much divisive as cohesive. The Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society (LASFS), dating from 1934, is the sole survivor of the clubs from this era.

So there was plenty of cause for feuding, and the members of "organized fandom" feuded to the hilt. How easily your reading tolerance can be overloaded with feuding, will govern whether you follow those sections closely or skim some of it.

In the sixteen months from December 1935 through March 1937, the field lost Stanley G. Weinbaum, Robert E. Howard, and H. P. Lovecraft — enthusiasts as well as strongly distinctive professional writers. In The Immortal Storm, their deaths pass as occasions for memorial fan publications, and concern (in Lovecraft's case) for the allowable use of unpublished fanzine contributions on hand. Guys like these don't come along every day — but again, the busily feuding fans are very young.

Many future SF professionals first popped up as major fans in the 1930s: Donald A. Wollheim (Ace Books, DAW Books) has a very prominent part in The Immortal Storm as perhaps Sam Moskowitz's main antagonist. Writers Ray Bradbury, James Blish, Frederik Pohl, Ross Rocklynne, Bob Tucker; artists Morris Dollens, Virgil Finlay; and dozens of others discovered "organized fandom". Lifelong fans like David A. Kyle and Harry Warner Jr. saw the light.

Toward the end of our book's period, current SF luminaries (especially in New York City) like John W. Campbell, L. Sprague de Camp, and Willy Ley began attending and publicizing the first tiny conventions. The Immortal Storm is packed with names (and there is an index as well as photos of dozens of young fans and pros).

Yes, all that stormy feuding was a tempest in a teacup. But science fiction fandom is still here, and science fiction would not be the same without it. There's nothing quite like it.

© 2006 Robert Wilfred Franson

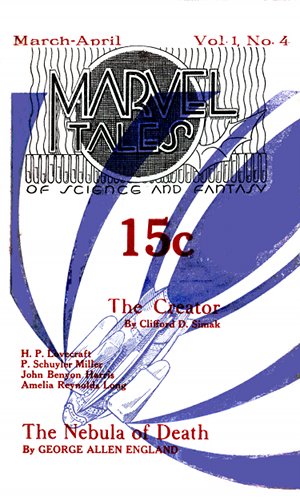

Marvel Tales cover, April-May 1935

This was one of William Crawford's intermittent semi-pro magazines. I think its logo backgruond consists of a row of test tubes with chemical fumes arising (representing science); on the right is a bat's wing (for fantasy).

Books which carry the fannish history forward with less feuding and more sociability are: Harry Warner Jr.'s All Our Yesterdays (1940s) and A Wealth of Fable (1950s). Frederik Pohl's science-fictional autobiography The Way the Future Was includes his time with the Futurians.

For a critique of the literature itself, the foundational work is Damon Knight's In Search of Wonder (1956; 1967; 1996).

ReFuture at Troynovant

history of science fiction

& progress of fantasy

The oldest national science-fiction club,

founded by Damon Knight in 1941:

National Fantasy Fan Federation

(NFFF, or more familiarly, N3F)

| Troynovant, or Renewing Troy: | New | Contents | |||

| recurrent inspiration | Recent Updates | |||

|

www.Troynovant.com |

||||

|

Reviews |

||||

| Strata | Regions | Personae |

|

|||